Test Fixtures

Make your tests more focused by moving sample data to pytest fixtures.

Each test recreates Player and Guardian instances, which is repetitive and distracts from the test's purpose. pytest fixtures give a rich infrastructure for your test data. In this tutorial step we convert our tests to use fixtures, which we then share between files using conftest.py.

Confirm PyCharm is in TDD-mode

Once again, check that your code is on the left, your test is on the right, your Run tool window is at the bottom and your tests are automatically running when there is a change to your code or tests.

Create a new fixture for Player and refactor test_player.py

In test_player.py we will make a new fixture for the player object:

@pytest.fixture

def player_one() -> Player:

return Player('Felicity', 'Smith', 16)

We now need to refactor our test code to use this fixture. Test functions request fixtures by declaring them as arguments. First, let's refactor our test_construction method to use the fixture:

def test_construction(player_one):

assert player_one.first_name == 'Felicity'

assert player_one.last_name == 'Smith'

assert player_one.jersey == 16

assert [] == player_one.guardians

Same again for test_add_guardian:

def test_add_guardian(player_one):

g = Guardian('Jennifer', 'Smith')

player_one.add_guardian(g)

assert player_one.guardians == [g]

And again for test_add_guardians:

def test_add_guardians(player_one):

g1 = Guardian('Jennifer', 'Smith')

player_one.add_guardians([g1])

g2 = Guardian('Mark', 'Smith')

g3 = Guardian('Julia', 'Smith')

player_one.add_guardians([g2, g3])

assert player_one.guardians == ([g1, g2, g3])

Last but not least, for test_primary_guardian:

def test_primary_guardian(player_one):

g1 = Guardian('Jennifer', 'Smith')

player_one.add_guardians([g1])

g2 = Guardian('Mark', 'Smith')

g3 = Guardian('Julia', 'Smith')

player_one.add_guardians([g2, g3])

assert g1 == player_one.primary_guardian

Pause and check that all your tests are passing after this refactor:

Create a new fixture for Guardian and refactor test_player

Now we have a fixture for the player object, it's time to make another for the guardian object in test_player.py:

@pytest.fixture

def guardians_list() -> list[Guardian]:

g1 = Guardian('Jennifer', 'Smith')

g2 = Guardian('Mark', 'Smith')

g3 = Guardian('Julia', 'Smith')

return [g1, g2, g3]

Next, refactor the tests that use the guardian object, starting with test_add_guardian to use the new guardians list:

def test_add_guardian(player_one, guardians_list):

player_one.add_guardian(guardians_list[0])

assert player_one.guardians == [guardians_list[0]]

Next up, test_primary_guardian:

def test_primary_guardian(player_one):

player_one.add_guardians([guardians_list[0]])

player_one.add_guardians([guardians_list[1], guardians_list[2]])

assert guardians_list[0] == player_one.primary_guardian

Once again, check all your tests are still passing:

Use Guardian fixture in our test_guardian.py class

Copy your guardians_list() fixture from test_player.py and then use Recent Files ⌘E (macOS) / Ctrl+E (Windows/Linux) to switch to test_guardian.py and paste the guardians_list() fixture there too. Let PyCharm handle the import for pytest as before:

@pytest.fixture

def guardians_list() -> list[Guardian]:

g1 = Guardian('Jennifer', 'Smith')

g2 = Guardian('Mark', 'Smith')

g3 = Guardian('Julia', 'Smith')

return [g1, g2, g3]

Finally, refactor your test_construction() method use the guardian fixture:

def test_construction(guardians_list):

assert guardians_list[0].first_name == 'Jennifer'

assert guardians_list[0].last_name == 'Smith'

Check that your tests all still pass:

You've probably noticed at this point that we have duplication. Don't worry, we're going to fix that in the next step!

Create a conftest.py file

A conftest.py file is used in pytest to share fixtures across multiple files. We're going to refactor our code to remove the fixtures from both our test_guardian.py and test_player.py files and move it into a single conftest.py file.

Since you're still in test_guardian.py, delete the guardians fixture guardians_list() from your code and then use Optimize Imports ⌃⌥O (macOS) / Ctrl+Alt+O (Windows/Linux) to remove any unused imports. Next use Reformat Code ⌘⌥L (macOS) / Ctrl+Alt+L (Windows/Linux) to tidy up an errant spacing issues. Don't worry - this will momentarily break your code but we will fix it!

Use Recent Files ⌘E (macOS) / Ctrl+E (Windows/Linux) to switch to test_player.py and cut both guardians_list() and player_one() fixtures from the file. Again, use Optimize Imports ⌃⌥O (macOS) / Ctrl+Alt+O (Windows/Linux) to remove any unused imports and Reformat Code ⌘⌥L (macOS) / Ctrl+Alt+L (Windows/Linux) to tidy up an errant spacing issues.

Go to your Project tool window ⌘1 (macOS) / Alt+1 (Windows/Linux) and at the root of your project, right-click and select New > File. You can filter the list by python by typing in "python" and then press ⏎ (macOS) / Enter (Windows/Linux). Call the file conftest (PyCharm will add the .py if you selected a python file) and press ⏎ (macOS) / Enter (Windows/Linux) again. PyCharm will create your new conftest.py file at the root of your directory.

Use PyCharm's Clipboard History ⌘⇧V (macOS) / Ctrl+Shift+V (Windows/Linux) and select the entry in the history that is both the fixtures you cut from your test_player.py file and paste them into the new conftest.py file. Let PyCharm handle the imports for you and use Reformat Code ⌘⌥L (macOS) / Ctrl+Alt+L (Windows/Linux) to keep everything tidy.

That's the end of the refactoring for conftest.py so now is a good time to check that all your tests are still passing.

Naming is hard

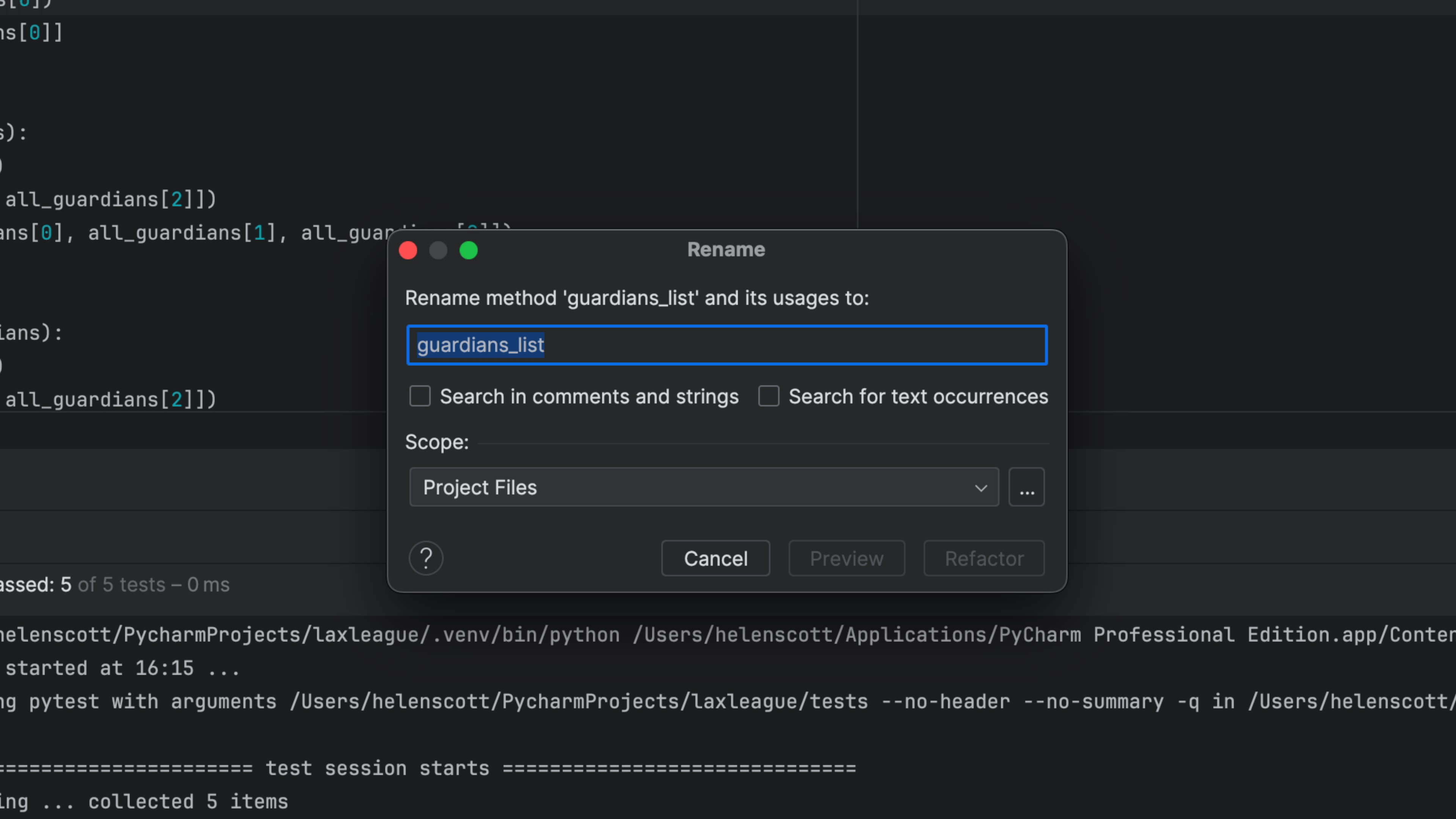

Before I leave you, naming is hard. I don't like the name guardians_list for my guardians fixture so in test_player.py I will select it, then use Refactor Rename ⇧F6 (macOS) / Shift+F6 (Windows/Linux) to choose a better name.

I'll go with all_guardians and then press Refactor:

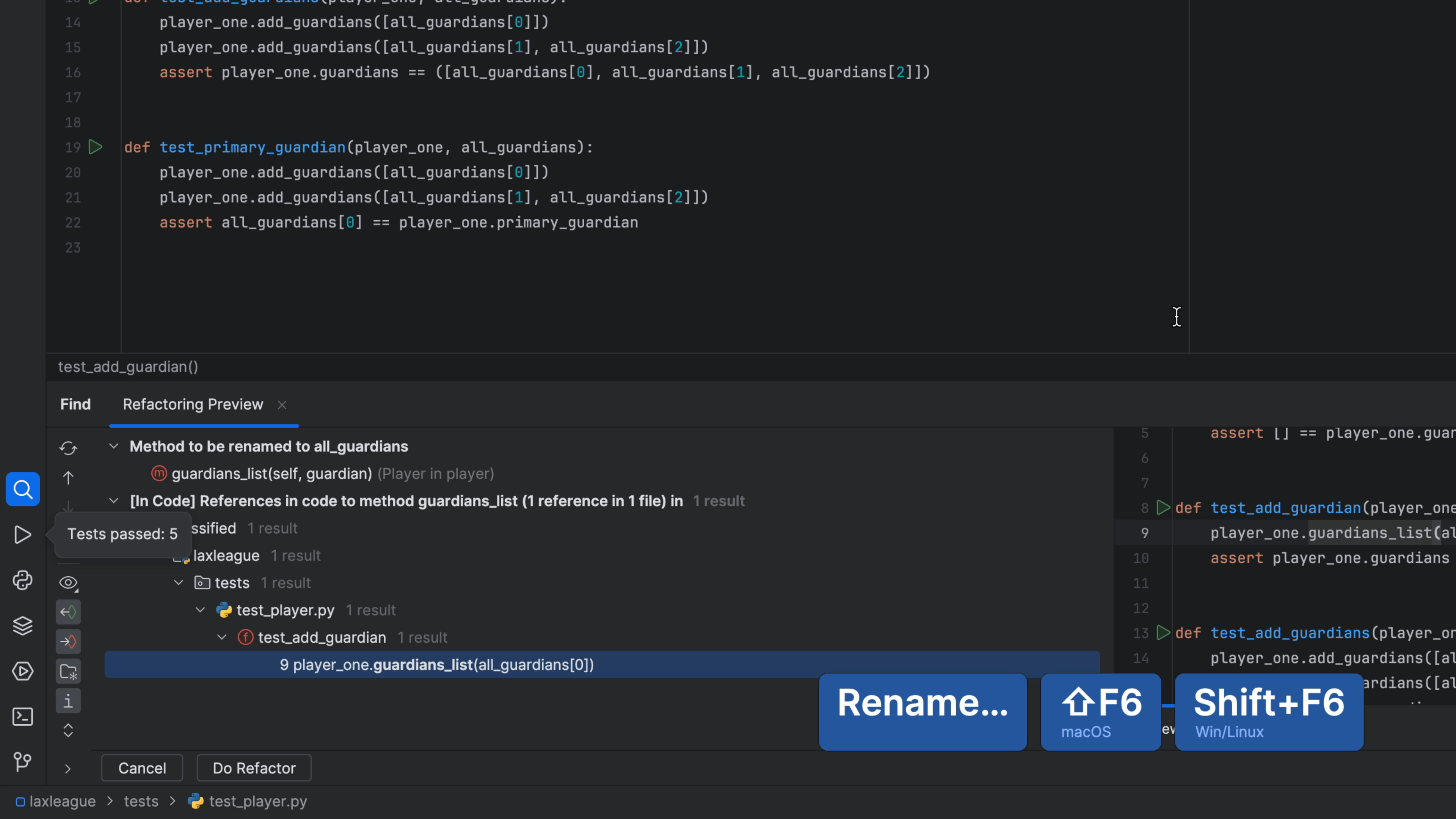

PyCharm now gives you a preview of which files will change and we can see that both our usages and the definition in conftest.py will be correctly updated:

Once you click Do Refactor, PyCharm, will update all of your code.

Final tip here, if you want to toggle between your usage and definition, you can hold down ⌘ or Ctrl and click in your editor.