Test Fixtures

Make your tests more focused by moving sample data to pytest fixtures.

Each test recreates Player and Guardian instances, which is repetitive and distracts from the test's purpose.

pytest fixtures give a rich infrastructure for your test data.

In this tutorial step we convert our tests to use fixtures, which we then share between files using conftest.py.

Make a Player Once

We have a Player instance that we currently make in four of our tests.

It's the same instance with the same arguments.

It would be nice to avoid repetition and let our tests focus on the logic under test, instead of setting up a baseline of test data.

Let's make a pytest fixture named player_one which constructs and returns a Player:

import pytest

from laxleague.guardian import Guardian

from laxleague.player import Player

@pytest.fixture

def player_one() -> Player:

return Player('Tatiana', 'Jones')

This fixture can now be used as an argument to your tests.

pytest will find the "appropriate" (more on this later) fixture with that name, invoke it, and pass in the result:

def test_construction(player_one):

assert 'Tatiana' == player_one.first_name

assert 'Jones' == player_one.last_name

assert [] == player_one.guardians

Our tests still pass.

We then make the same change in the other tests, taking the player_one fixture as an argument instead of constructing a Player in the test body.

Let's next make a fixture to hold the Guardian list:

from typing import Tuple

import pytest

from laxleague.guardian import Guardian

from laxleague.player import Player

@pytest.fixture

def player_one() -> Player:

return Player('Tatiana', 'Jones')

@pytest.fixture

def guardians() -> Tuple[Guardian, ...]:

g1 = Guardian('Mary', 'Jones')

g2 = Guardian('Joanie', 'Johnson')

g3 = Guardian('Jerry', 'Johnson')

return g1, g2, g3

After converting all the tests to use these fixtures, our test_player.py looks like the following:

import pytest

def test_construction(player_one):

assert 'Tatiana' == player_one.first_name

assert 'Jones' == player_one.last_name

assert [] == player_one.guardians

def test_add_guardian(player_one, guardians):

player_one.add_guardian(guardians[0])

assert [guardians[0]] == player_one.guardians

def test_add_guardians(player_one, guardians):

player_one.add_guardian(guardians[0])

player_one.add_guardians((guardians[1], guardians[2]))

assert list(guardians) == player_one.guardians

def test_primary_guardian(player_one, guardians):

player_one.add_guardian(guardians[0])

player_one.add_guardians((guardians[1], guardians[2]))

assert guardians[0] == player_one.primary_guardian

def test_no_primary_guardian(player_one):

with pytest.raises(IndexError) as exc:

player_one.primary_guardian

assert 'list index out of range' == str(exc.value)

Our tests are now easier to reason about.

Sharing Fixtures with conftest.py

Next we give test_guardian.py the same treatment:

from typing import Tuple

import pytest

from laxleague.guardian import Guardian

@pytest.fixture

def guardians() -> Tuple[Guardian, ...]:

g1 = Guardian('Mary', 'Jones')

g2 = Guardian('Joanie', 'Johnson')

g3 = Guardian('Jerry', 'Johnson')

return g1, g2, g3

def test_construction(guardians):

assert 'Mary' == guardians[0].first_name

assert 'Jones' == guardians[0].last_name

Hmm, something looks wrong.

We said fixtures helped avoid repetition, but this guardians fixture is the same as the one in test_player.py.

That's repetition.

Is there a way to move fixtures out of tests, then share them between tests?

Yes, in fact, multiple ways.

The simplest is with pytest's conftest.py file.

You put this in a test directory (or parent directory, or grandparent etc.) and any fixtures defined there will be available as an argument to a test.

Here's our tests/conftest.py file with the fixtures we just added in test_player.py:

from typing import Tuple

import pytest

from laxleague.guardian import Guardian

from laxleague.player import Player

@pytest.fixture

def player_one() -> Player:

return Player('Tatiana', 'Jones')

@pytest.fixture

def guardians() -> Tuple[Guardian, ...]:

g1 = Guardian('Mary', 'Jones')

g2 = Guardian('Joanie', 'Johnson')

g3 = Guardian('Jerry', 'Johnson')

return g1, g2, g3

Now our test_guardian.py is short and focused:

def test_construction(guardians):

assert 'Mary' == guardians[0].first_name

assert 'Jones' == guardians[0].last_name

Same for test_player.py:

import pytest

def test_construction(player_one):

assert 'Tatiana' == player_one.first_name

assert 'Jones' == player_one.last_name

assert [] == player_one.guardians

def test_add_guardian(player_one, guardians):

player_one.add_guardian(guardians[0])

assert [guardians[0]] == player_one.guardians

def test_add_guardians(player_one, guardians):

player_one.add_guardian(guardians[0])

player_one.add_guardians((guardians[1], guardians[2]))

assert list(guardians) == player_one.guardians

def test_primary_guardian(player_one, guardians):

player_one.add_guardian(guardians[0])

player_one.add_guardians((guardians[1], guardians[2]))

assert guardians[0] == player_one.primary_guardian

def test_no_primary_guardian(player_one):

with pytest.raises(IndexError) as exc:

player_one.primary_guardian

assert 'list index out of range' == str(exc.value)

Life With Fixtures

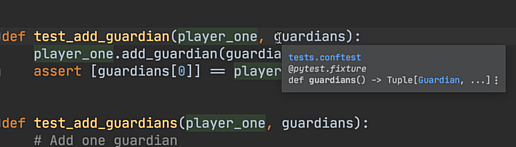

PyCharm has a number of useful features that make working with fixtures a breeze. We saw autocomplete. This is even more important with all the places that pytest can look for fixtures.

Navigation is a big win, for the same reason. Cmd-Click (macOS) on a fixture name and PyCharm jumps to the fixture definition. Same applies for hover which reveals type information.

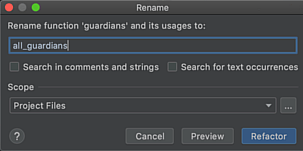

F1 (macOS) / Ctrl+Q (Windows/Linux) on the fixture shows an inline popup with more information about the fixture. Finally, you can Refactor | Rename to change the fixture's name and usages.

This is all driven by PyCharm's type inferencing, which means we can autocomplete and give warnings in the test body, based on the structure of the fixture. In practice, this is a key part of "fail faster", meaning, find a problem before running (or even writing) a test.